By Ronan O'Gara

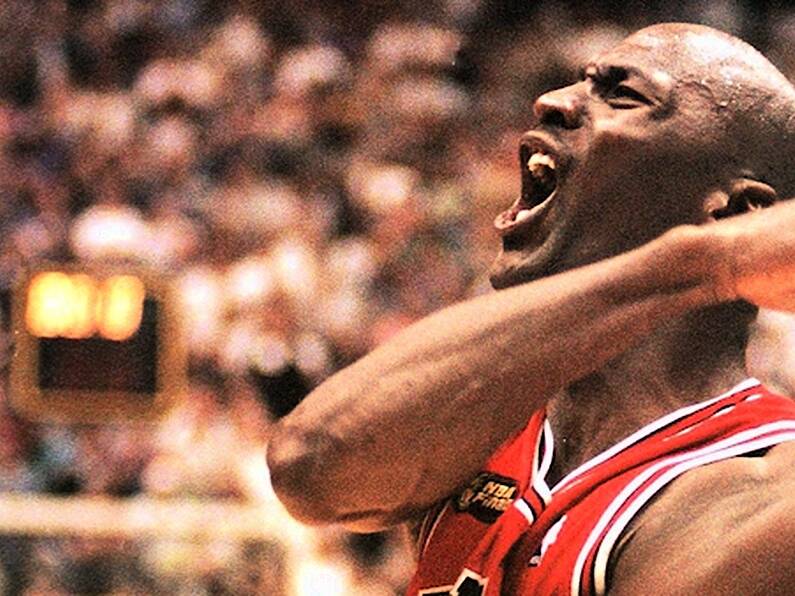

In typical O’Gara fashion, the week we come out of lockdown in France I start binge-watching series on Michael Jordan and his impact on the Chicago Bulls locker room.

I love this stuff. The teaser of Jordan explaining how winning and leadership comes at a price had me hooked. It is so true.

From what I’ve heard and seen so far, No. 23 wasn’t slow to call out a colleague he felt might be jeopardising his, and the team’s, prospects of success. I’m fine with that. I spent my playing career in a dressing room of strong personalities and leaders.

It was a few years after the Bulls were in their pomp. Things that were okay to lay on someone then would be interrogated more nowadays. But in any era, an ambitious dressing room should never be confused with a library or a confession box. It’s a combustible

cocktail of fires, personal and group goals and the central character keeping it together is the coach.

Hence why Phil Jackson’s status can only be enhanced by .

We had moments in that successful Munster dressing room. The outbursts were never calculated though, even in training. Or it might be a video review session if you felt something had to be called out. It was always for the right reasons, even if poorly articulated on occasions. You can’t feign fury.

Importantly, the group ensured that things never festered. You could snap at a guy, and I did regularly, but worst-case scenario you’d pick up a phone on the way home and say sorry about that, it didn’t come out well at all.

I said stuff when the red mist blinded my perspective and deactivated my filter. Stuff that you would never want to repeat. One day in Dooradoyle, I abused Alan Quinlan, but I felt I had to bury him there and then.

He was lining up with the second team and he was messing up all our plays. “That’s why you are on that side of the pitch, you absolute bleep bleep.”

Wow. Imagine saying that.

Going to Australia with the Lions in 2001 was an important turning point.

The level of standards and professionalism from some of the English lads drove home that there was more to this lark than the standards I was operating at to that point. Some of the best players were also the most professional in terms of their standards and consistency.

There was a real refocus period afterwards for me. When I came home to Munster there was a fork in the road — keep that going within my own group or revert to accepted norms. It wasn’t just a learning curve for me — consistency of message and performance were ingredients we needed to bring into our Munster dressing room.

It was an environment hungry to learn. The work ethic of the group gave us a good platform to build from. Plus, we had a voracious appetite to improve having lost the previous year’s European Cup final at Twickenham.

It’s easy to see that pathway now given what Irish rugby has done, but back then there wasn’t much of a success chart or a template to work from. We had plucky one-off wins but nothing in terms of building sustainability. That’s where the group leadership came in. Paulie hadn’t come in yet — he would add to the mix soon after — but there was already a united goal and a common purpose.

This was a steep learning curve in the early noughties but being in on the ground floor bestowed a certain level of dressing room leadership that one didn’t actively pursue. If anyone sought to mark out their territory on a higher plane, they were cut down at the knees without questions or delay. The one place where getting above your station does not exist would be a Munster dressing room.

Also, I had the room to grow. There was never an over-dependence on the 10 for leadership or direction. I knew, as did everyone, that if there is an over reliance on a 10, and he has an off-day, then the ship is sunk. Plenty of performances we know of have suffered in that regard.

I was never slow to voice my opinion and when things irked me, either from the coach or the players. I had my say. I would drive home raging when I’d hear about us poor Munster underdogs. I wanted to be more ‘let’s take the favourite mantle and beat these guys’. You got tired of being David against Goliath after a bit. When we were expected to win games, I felt we should embrace

favouritism, not avoid it.

Jordan’s collegiate talents advertised his arrival in Chicago but he still had to earn the right to be The Man over time. You have to know your place first off. That comes before earning the right to call out something. And then you must seize that moment. If you do that consistently, you earn peer respect.

Sometimes you’ve just to call it and say that’s rubbish. The difference between someone doing that for the greater good and others who feel it necessary (out of their own insecurity) to score points is night and day. The latter soon come across as spiteful, and that is a horrendously bad trait in a dressing room.

HE bad apples never lasted in Munster. There were one or two along the way, but they got weeded out. There were too many good eggs. The leadership group would suss that someone needed to be pulled aside and carpeted. Poisonous behaviour has the potential to destroy everything, not just its primary target.

But it’s understanding the dressing room, understanding the difference between who should speak and who needs to speak. There were some colleagues — sorry I didn’t have ‘colleagues’, they were team-mates or brothers — who liked to work themselves into a froth before the game, and you heard them out because it was important for them to vent. But just as important was that they didn’t limit the time of the leaders we should be hearing from. There was invariably someone who was going to pipe up and talk absolute shite but that was important for them in their preparation. It also underlined that this was a democracy.

I made buckets of errors in terms of speaking out of turn. I was spicy enough with one or two lads. If you are wrong, you can’t let it fester. At Munster, we had the kiss ‘n make up ritual at the end of training. Excruciating stuff at times but necessary in hindsight. There might have been three different barneys in the session between six players, So I’d have to go to Quinny and kiss him on the lips. Sometimes you’d be stewing, and the cold hugs would say as much. But there was no getting away, even with a secondary peck on the cheek. It had to be the lips.

I’d be like an anti-Christ after training on occasions. You’d apply the 24-hour rule — ie letting the hare sit — in the hope you’d have calmed down by that time. Odd that it only really started working for me when I turned 40.

During , there were locker room moments when you weren’t quite sure whether Jordan was being serious or hopping balls. When the new Thomond Park opened, we had our own dressing room cubicles. I liked having my own spot. Small stuff like being shunted around can wreck your head. It was a comfort blanket for creatures of habit. But that didn’t stop the smart arses telling a Munster rookie ‘sit down over there, you’re grand’, knowing that it was my spot.

Then our so-called ‘leaders’ would crack open the popcorn and wait for my reaction.