A group of scientists from across the globe lead by colleagues from UCC have revealed a submarine canyon 320km west of Dingle, within which they say you could stack 10 Eiffel Towers.

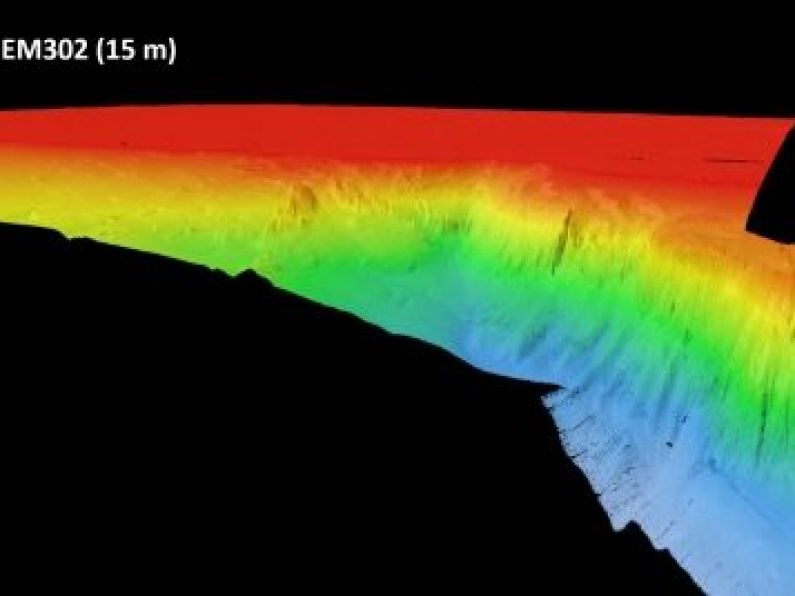

After mapping an area twice the size of Malta, or 1800 km2, on board the RV Celtic Explorer over a fortnight, they revealed a canyon which is 3,000 metres deep.

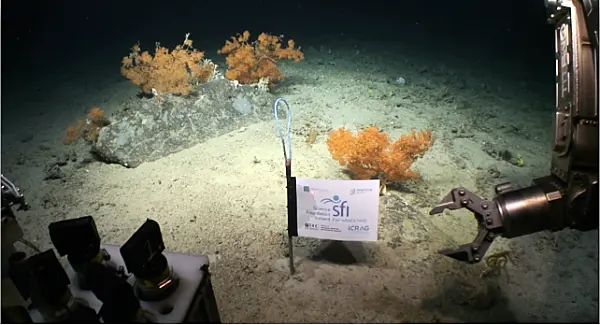

The expedition, led by Dr Aaron Lim of UCC’s School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences (BEES), used the Marine Institute’s Holland 1 Remotely Operated Vehicle (ROV) .

They said the find will help them understand more about how it helps transport carbon to the deep ocean.

They said that the excess CO2 in the atmosphere, due to the greenhouse effect, is being absorbed by the surface of the ocean, and canyons pump this into the deep ocean where it cannot get back into the atmosphere.

Dr Lim said: “This is a vast submarine canyon system, with near-vertical 700m cliff in places and going as deep as 3000m.

"You could stack 10 Eiffel towers on top of each other in there.”

“So far from land, this canyon is a natural laboratory from which we feel the pulse of the changing Atlantic.”

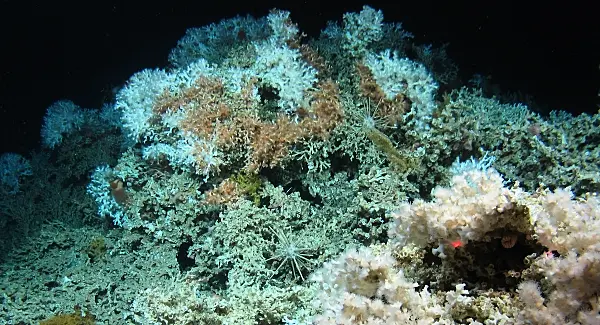

The Porcupine Bank Canyon is full of cold-water corals forming reefs and mounds which create a rim on the lip of the canyon 30m tall and 28 km long.

The coral reefs on the rim of the canyon eventually break off and slide down into the canyon where they form an accumulation of coral rubble deeper within the canyon.

The ROV ventured deeper into the canyon and found significant build-ups of coral debris that have fallen from hundreds of meters above.

“This is all about transporting carbon stored cold water corals into the deep. The corals get their carbon from dead plankton raining down from the ocean surface so ultimately from our atmosphere,” said Professor Andy Wheeler, School of BEES, UCC, and the Irish Centre for Research in Applied Geosciences (iCRAG).

“Increasing CO2 concentrations in our atmosphere are causing our extreme weather; oceans absorb this CO2 and canyons are a rapid route for pumping it into the deep ocean where it is safely stored away.”

The new detailed maps show lobes of sediment debris and the scars from submarine slides as the canyon walls collapse.

They also show exposed old crustal bedrock and incised channels in the canyon floor carved by sediment avalanches.

What the Porcupine Bank Canyon would look like with the sea drained out with steep cliffed edges and cold-water coral mounds in the top.

Professor Wheeler said: “We took cores with the ROV, and the sediments reveal that although the canyon is quiet now, periodically it is a violent place where the seabed gets ripped up and eroded.”

The new mapping data shows a rim feature along the lip of the canyon around 600m down.

Professor Luis Conti, University of Sao Paulo, said: “When we sent down the ROV, we saw that this rim is made of a profusion of cold water corals, which appears to extend for miles along the edge of the canyon.”