By Dominic McGrath, PA

The scientists recruited by the Government to spread Covid-19 messaging on TikTok and Instagram have spoken of the level of misinformation and abuse they encountered online.

The creators behind the novel communications strategy, which saw the Department of Health dabble in public health messaging across social media, also told PA news agency how difficult the pandemic has been for young people.

The SciComm Collective, launched in the first half of last year, was intended to get the Government’s Covid-19 messaging out to young people through platforms such as Instagram and TikTok.

It was also a key part of an attempt to dispel myths and misinformation about Covid-19 and vaccines.

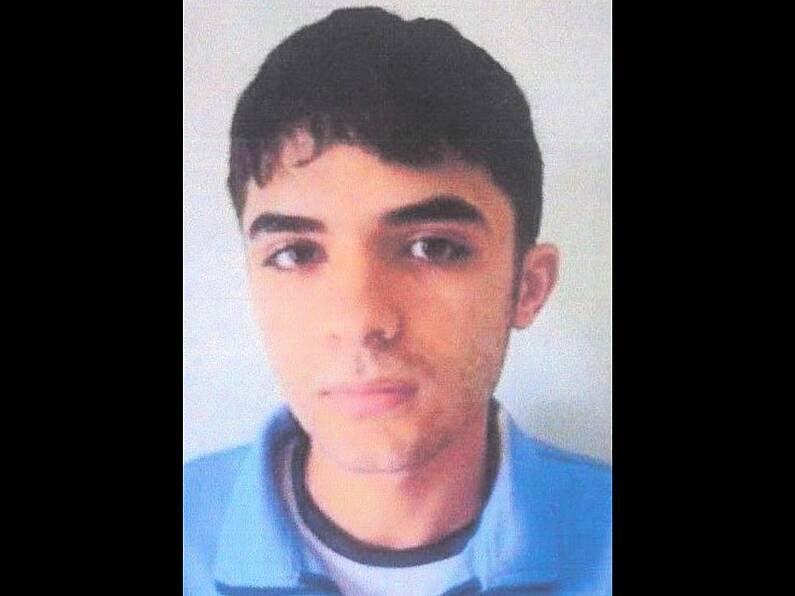

Andrew McGovern, a 27-year-old PhD researcher at the University of Limerick, started out with a podcast in February 2021, before getting a surprise email from the Department of Health.

“I was a little bit like, ‘Excuse me. Is this a scam?’ It was very out of the blue.

“At the time I was teaching in UL, I was a teaching assistant on the bioscience programme, so it wasn’t that far out of my area. And I had done a few little videos about Covid.”

Now Mr McGovern is a regular presence on the smartphone screens of his 20,000 followers – posting frequent updates and explainers from his own personal TikTok account, as well as appearing on Department of Health platforms.

“They never told us explicitly, ‘you need to make a video about this or you need to make a video about that’,” he says.

It has prompted a largely positive working relationship and he praises Government communications during the pandemic overall.

While he says that there was not a “tension” with the Department of Health, there was often a lack of room for “nuance” when making videos.

“If you were in the position of, let’s say, the Government or the department, you can’t make a statement with nuance when you’re trying to explain something and what the public in general should do.

“You can’t explain the nuance so well, because people will jump on that and hold it against you and it weakens the reason we’re doing it, and even if there is nuance in it, it’s better that we follow public health advice.”

He says that when he made videos for the Government, he was careful not to “blur the message”.

“On my personal TikTok, it was more so ‘Look lads, it’s not perfect, but it does make sense’.

“And then I talked through it and I’m like – look sure we could be doing this, that and the other but we do know that this works so we might as well go for it.

“It’s something that gave me an advantage when I did my own ones.”

The reluctance of Irish health officials to give vocal backing to antigen testing is a case in point, he says.

The description of antigen testing as “snake oil” by National Public Health Emergency Team (Nphet) member Prof Philip Nolan, Mr McGovern says, “shouldn’t have been said”.

“What the big problem there was, the communications was awful.”

“What should have been said was ‘we’re keeping an eye on it, the evidence right now doesn’t justify it being a public health measure’.

“The thing is, at the time, if you go back to just the evidence they had then, it was a fair enough statement to say that.

“We’re seeing now that it’s much more useful. It takes time to develop this confidence.”

Mr McGovern says that people should realise that it would not be right for the Government to back any public health measure if the “evidence is not 100%”.

“The problem is, in some circumstances, maybe someone misspoke or someone said something slightly poorly.

“And when you’re trying to communicate to five million people, if you misspeak, or you say something slightly wrong, or you say something that can be misinterpreted, that’s exactly what’s going to happen. ”

“Some people are going to say it’s wrong.”

He thinks the Government was right to realise, though, that public health messaging delivered by savvy scientists on social media would cut through to young people better than any briefing from chief medical officer Dr Tony Holohan.

More importantly, as someone who was in his mid-20s when the pandemic began, he understands the sacrifices many people made.

“I think it’s been very unfair, and it’s been very hard to come to terms with. A lot of it’s been having something stolen from you. You can’t use years of your life that you’re meant to be kind of carefree. ”

Dr Rafael de Andrade Moral, a 32-year-old mathematics lecturer at Maynooth University, took science communication to heart early on.

He remembers having to record lectures when the pandemic began, but realising how boring they were.

“So I decided to sing about it. That’s when I put the first song up. I filmed my rabbits because I have two pet rabbits, two dogs.

“People seemed to like it.”

His efforts have grown from there. In one video he discussed the different types of vaccines to the tune of a Backstreet Boys song.

Originally from Brazil, he says his family and friends at home have enjoyed the videos.

The Department of Health, he says, tapped into something much needed for communicating the complexities of the pandemic.

Nonetheless, he was “surprised” when the Government got in touch.

“I thought that that was exactly what we needed at the time and I think it was really successful in terms of the engagement we got.”

Dr Megan Hanlon is a 27-year-old researcher in immunology at Trinity College Dublin.

When the pandemic hit, she moved back to her family farm in Co Westmeath. With her PhD completed, she started on a new project – a podcast in which she interviewed fellow scientists.

That experience led her to the Department of Health, where she says it was a “big learning curve” to go from podcasts to videos and TikToks.

“One thing that was on my side was my sister is 16. So anytime I would do anything, any videos, she would like, judge them and be like, ‘No, that’s crap’.”

Young people, she says, have been a key audience throughout the pandemic.

“They’re not really watching the news. They’re not watching the public health briefings. They’re getting a lot of information and importantly, a lot of mis and disinformation, from social media.”

She praises the Department for giving the creators space for discussion and disagreement, but admits that dealing with trolling online was “difficult”.

After a few videos triggered abuse, she decided not to put her face in her next few posts.

She describes it as “a lot of people going, ‘this is fake’ or ‘you shouldn’t be doing this’.”

“It’s directed at the Government,” she says.

“It wasn’t personal towards me, but there was a few personal comments. A lot of people did struggle with that.

“I’m not used to something like that.”

Despite that, she believes it was a “brilliant” experience and praises the Government for backing it.

“I loved it, it was a great experience.

“Just to be able to help out and do your bit.”