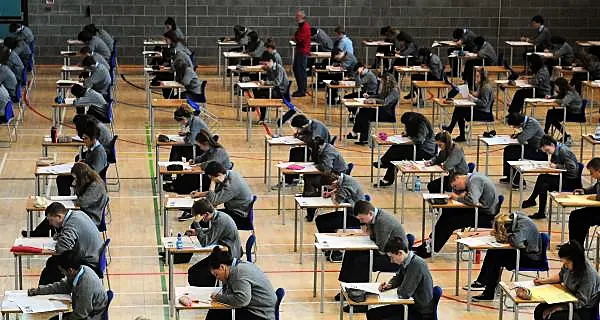

Teachers can finally start processing grades for thousands of Leaving Cert students after they were given further assurances from the Government that they will be protected from legal action.

After getting assurances that teachers will not be liable for costs if they are named in civil proceedings, the Association of Secondary Teachers, Ireland (ASTI) directed its members to begin working on the calculated grades process.

“Unfortunately, the indemnity that was offered to teachers on Thursday fell short of what is required,” said ASTI general secretary Kieran Christie.

“We had requested that the issuing of the guidelines be held off until the matter was resolved.”

Following talks with the Department of Education, the ASTI believes clear assurances have now been made that allow teachers to proceed, without the fear of negative financial consequences, he said.

The department has agreed that the Chief State Solicitor’s Office will take over the running of litigation in all cases where the indemnity applies, according to Mr Christie.

This means that a teacher will not have to employ their own legal team to defend themselves, or run the risk of incurring large irrecoverable costs and expenses, he said.

The Teachers’ Union of Ireland (TUI), whose members are already engaged in this work in schools, said its position on calculated grades has been vindicated.

The union also sought assurances from the Department of Education, including that the protections for teachers as referenced in the indemnity, extend to principals, deputy principals, Youthreach resource persons, co-ordinators, tutors, and lecturers.

“In this context, the union sought and has received confirmation that the Chief State Solicitor’s Office will act for the teacher in every instance in which the indemnity applies”, the TUI said, adding that the protections will apply to all staff involved in the calculated grades process.

The step forward will come as some relief to 61,000 students and their families.

Students will next week be asked to register for calculated grades online if they wish to be assessed under this model.

It was also welcomed by Joe McHugh, the Minister for Education, who said the agreement allows for progress onto the next stage of this year’s alternative assessments.

“I’m happy now to say that everybody is in agreement in terms of the level of security around the indemnity for teachers, and also for schools and boards of management,” he said.

Mr McHugh accepted that this controversy has added to the stress levels for Leaving Cert students, but defended his handling of the matter. He said it would have been a “dereliction of duty” to have cancelled the exams without a finalised back-up plan. It was always his preference for the exam to begin in June, he said.

“That was my plan A,” he said. “There was the uncertainty around Covid, and certainly at a time when we didn’t know where it would be in terms of the curve in terms of the numbers of people who would be infected, we postponed the Leaving Cert to the end of July, beginning of August.

“It was the preferred preference of mine from day one for the written exam to go ahead with what we have to do. Then we had to model what the Leaving Cert would look like under the specific public health guidelines. It was a Leaving Cert that the State Examination Commission couldn’t stand over.

“It was a Leaving Cert that didn’t have validity. So therefore, it wasn’t adhering to the expectation of the student for the work that they’ve done over two years,” he said.

The calculated grades system is considered to be a relatively time-sensitive process, with the Department of Education asking schools to have the required data submitted to it as close as possible to the end of May.

Analysis: A step into the estimated unknown

Jess Casey

Teachers’ estimates can be unconsciously affected by what they know or think about a student’s family or socio-economic background, according to the official guidelines.

The Department of Education maintains that the estimated marks a student receives cannot be seen as results given by an individual teacher, as they are examined, compared, and verified through several stages.

At the same time, its official guidance on how to grade students reminds teachers to be aware of their “unconscious bias” when deciding a student’s marks.

Teachers’ estimates can be unconsciously affected by what they know or think about a student’s family or socio-economic background, according to the official guidelines.

Estimates can also be affected by the teacher’s perceptions of a student’s behaviour in class, it adds. The official guide instructs teachers to base their grade estimations on evidence, but then later adds that “not all forms of evidence will be grounded in records”.

When it comes to students’ past results in exams, assessments, and — “with some caution” — mocks, teachers are also asked to take into account the quality of each of these tests, as well as the level of difficulty and “the purpose” each test in question was designed to serve.

At times, the guidelines are maddeningly ambiguous. This includes instructions on how to grade a student’s performance on coursework, even if it is not complete.

A teacher’s professional judgement on a student’s performance may also be informed by comparing a student this year to a student in a previous year of a similar ability, and how that student got on in the final exam.

When marking students, teachers can take into account projects or activities that a student did that enhanced their knowledge of a subject, “improving likely performance”.

How do you quantify a decision based on these factors? And in previous years, the majority of this work would never have been considered as part of a student’s final grade in a subject, the majority of which is usually determined by a single exam.

Then take into account the fact that teachers know their students well, know how much a student wants a certain course and the fact that they are being asked to embark on this completely new process, all while operating on a tight deadline.

It is also important to point out that the Department of Education is expecting legal action.

Education Minister Joe McHugh signalled as much when he announced the cancellation of the exams.

Technically speaking, you have a right to challenge anything legally, so you could speculate that this concession might be taken to mean it is expected that there will be successful legal actions taken over calculated grades.

The consultation process around developing the calculated grade guidelines is said to have been painstaking, a round-the-clock process that took feedback into account. Calculated grades are not anyone’s preferred option, rather the best system developed quickly in lieu of a written exam it is not safe to hold during a pandemic.

Now there is collective unity around the protections on offer, it is a happy step forward. However, it is likely that we might yet encounter more stumbling blocks. It is a completely new system and more clarification may be needed along the way, Mr McHugh said yesterday.

“It’s a system that’s not perfect because we’ve had to do it in such a short period of time,” he said.

The Department of Education maintains that the estimated marks a student receives cannot be seen as results given by an individual teacher, as they are examined, compared, and verified through several stages.

At the same time, its official guidance on how to grade students reminds teachers to be aware of their “unconscious bias” when deciding a student’s marks.

Teachers’ estimates can be unconsciously affected by what they know or think about a student’s family or socio-economic background, according to the official guidelines.

Estimates can also be affected by the teacher’s perceptions of a student’s behaviour in class, it adds. The official guide instructs teachers to base their grade estimations on evidence, but then later adds that “not all forms of evidence will be grounded in records”.

When it comes to students’ past results in exams, assessments, and — “with some caution” — mocks, teachers are also asked to take into account the quality of each of these tests, as well as the level of difficulty and “the purpose” each test in question was designed to serve.

At times, the guidelines are maddeningly ambiguous. This includes instructions on how to grade a student’s performance on coursework, even if it is not complete.

A teacher’s professional judgement on a student’s performance may also be informed by comparing a student this year to a student in a previous year of a similar ability, and how that student got on in the final exam.

When marking students, teachers can take into account projects or activities that a student did that enhanced their knowledge of a subject, “improving likely performance”.

How do you quantify a decision based on these factors? And in previous years, the majority of this work would never have been considered as part of a student’s final grade in a subject, the majority of which is usually determined by a single exam.

Then take into account the fact that teachers know their students well, know how much a student wants a certain course, and the fact that they are being asked to embark on this completely new process, all while operating on a tight deadline.

It is also important to point out that the Department of Education is expecting legal action.

Education Minister Joe McHugh signalled as much when he announced the cancellation of the exams.

Technically speaking, you have a right to challenge anything legally, so you could speculate that this concession might be taken to mean it is expected that there will be successful legal actions taken over calculated grades.

The consultation process around developing the calculated grade guidelines is said to have been painstaking, a round-the-clock process that took feedback into account. Calculated grades are not anyone’s preferred option, rather the best system developed quickly in lieu of a written exam it is not safe to hold during a pandemic.

Now there is collective unity around the protections on offer, it is a happy step forward. However, it is likely that we might yet encounter more stumbling blocks. It is a completely new system and more clarification may be needed along the way, Mr McHugh said yesterday.

“It’s a system that’s not perfect because we’ve had to do it in such a short period of time,” he said.