A Dublin couple who gave up their baby boy for adoption when they were teenagers have found him again, 36 years later.

Their extraordinary story has culminated in an emotional meeting with their son, who was adopted in the midlands and who has now met his birth parents and four full siblings for the first time.

The “fantastic, amazing, hugely emotional” reunion after so long came about mostly through the couple’s own efforts, after they were left frustrated by delays in the official process.

Maria* was 16 when she became pregnant in 1979. It was still the era of mother and baby homes, where many pregnant girls were sent to deliver their babies and, most often, surrender them for adoption.

Maria was placed in one of those homes - Dunboyne in Co Meath, run by the Good Shepherd sisters. She stayed for six months, and delivered her baby boy in the summer of 1980.

*Names have been changed in this story to protect the privacy of those involved.

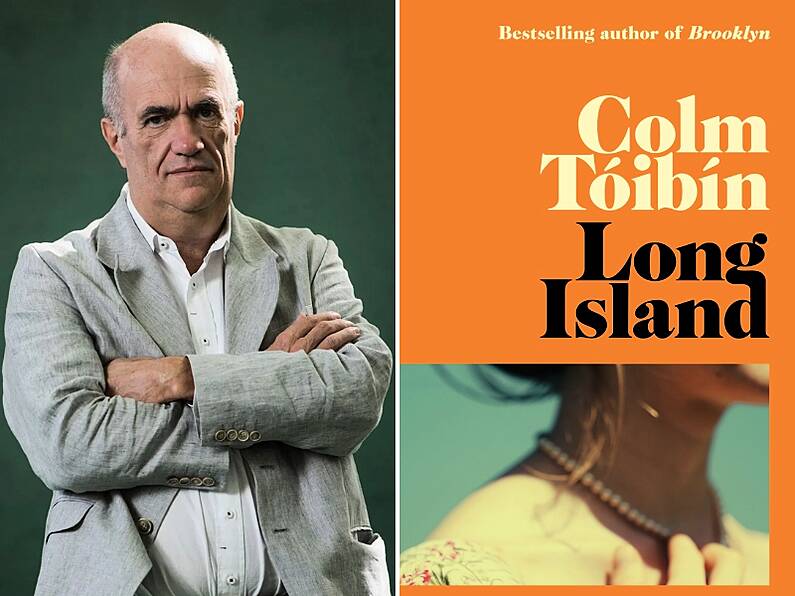

Stock image

’The best they could’

Her parents and a priest who was a family friend arranged it all. Maria says she bears no bitterness towards them and in fact remembers her mother especially with great love.

“They were Catholic parents who did the best they could at the time, and the whole society was very different,” she said. “They didn’t intentionally hurt me - I was the eldest, just starting my life, and they wanted to protect me, no matter what.

“My mum especially was kind and good...I feel no bitterness towards them.”

Nonetheless, Dunboyne was a lonely experience for Maria. Girls had their names changed while they were there and were told not to discuss anything or anybody from their personal life, she says.

Family, close friends and the priest who helped arranged her stay in the home visited her during her time there, but her ‘normal’ life was on hold.

(We put a series of questions to the Good Shepherd sisters about the treatment of girls in their care in Dunboyne and received the following statement:

"The Good Shepherd will continue to deal directly with the Commission on all matters relating to mother and baby homes, and will have our fullest co-operation. The related documents are no longer in our possession; they are now held by TUSLA"

The adoption

Maria gave birth to Paul* in Holles Street in 1980 and kept him with her for five days. On the fifth day, he was placed for adoption with the St Patrick’s Guild adoption society, and cared for in St. Patrick's Infant Hospital, Temple Hill until an adoptive family was found. Maria returned to Dunboyne to complete her Leaving Cert, and then went home.

No pictures, no momentoes

“I knew he was going to Temple Hill, and that’s all I knew,” she said. “I signed one set of papers and my mum told me I could take him back before I signed a second set a few weeks later,” she said. Maria says she was advised by the nuns to take no pictures, and so had no momentoes of her son.

“A dreadful emotional memory” is how Maria describes the day she passed Paul over for adoption. She says she felt he was “snatched” from her arms without a proper goodbye.

The aftermath - a ‘big, dark secret’

In the time that followed, Maria felt unable to discuss her experience with anyone. Her mother tried a few times, but Maria shut the conversation down.

She had only one friend who knew more than anyone how Maria felt. Otherwise, the experience was essentially “a big, dark secret...There was a feeling of complete shame, and trauma too”, she remembers.

“Something like this affects you your whole life, every day...You only had the memories in your own head. The nuns said not to take a photo, so I didn’t. I was young...I had nothing to remember him by.”

Maria remembers neighbours who had adopted children who they clearly cherished and loved. “That vision kept me going,” she said, “that he was in a house like that. That he was loved.”

She and Paul’s father Mark* stayed together - all the while not discussing what had happened in any depth. Maria says she just couldn’t handle Mark’s emotion as well as her own, so they simply didn’t discuss it.

They became pregnant again two years later. This time, they kept their baby, got married and went on to have three more children.

Maria experienced profound postnatal depression with two of her subsequent children - the two boys - and believes it was triggered by the circumstances of Paul’s birth, and his adoption. Still, even under the care of a psychiatrist in a mental health facility, she was unable to talk in any depth about Paul’s birth and adoption. Her psychiatrist described her as a “closed book”.

Image posed by model

Finally, after the birth of her fifth and last child - a girl - Maria felt something “opening up” inside her. She still could not talk freely about Paul’s adoption - even with her husband - but it was the start of a process that led her to start searching for her baby boy.

’I’d wonder if he was dead’

“For many years, I thought about him all the time, especially on his birthday, at Christmas and Easter - all the special occasions,” Maria said. “I’d wonder if he was dead. I heard nothing though - I’d asked for photographs, but nothing came.”

Then, in the late 1990s, the Adoption Authority of Ireland sent out forms to people who had participated in adoptions, on which birth parents could leave their name and address if they were willing to be contacted by their children. Maria filled in the form and sent it back, and although nothing came from it directly, it marked the beginning of her search.

When Maria’s elder daughter became pregnant for the first time seven years ago, Maria told her about Paul, and describes it as “the biggest relief in the world”, but immediately shut down again afterwards and could not discuss it any further. Her other three children - Paul’s two brothers and sister - only found out recently. Maria had been terrified of their reaction - what they would think about her, and how they would react emotionally to the existence of an unknown brother.

The key event was Maria’s own mother’s Alzeihmer’s and death in 2014.

“Mammy had wanted to meet him, but never did. And once she got Alzeihmer’s I lost the chance to talk to her about it,” Maria says, her voice breaking.

’Obsessed’ with idea of finding her son

By now determined to find out what happened to her son, Maria’s first stop was Barnardos for advice, but after so many years of keeping her secret, it was difficult to jump straight in, and again she withdrew.

Over the next year or so, Maria began telling a few people her story - a couple of cousins and friends. She was buoyed by their support and again approached Barnardos for advice. She and Mark went together, and Maria cried through the whole meeting. Mark took notes, and finally they had a starting point. Unfortunately for them, it was in the middle of a handover process of the St Patrick’s Guild adoption records to Tusla - a process now complete, but which took two years to effect.

Maria was told there were still more than 5,000 records to go through (of an initial 13,000), and a waiting list of parents with queries. Tusla prioritises requests from people over 70 or who have life-threatening illnesses.

After so many years of locking away her story, Maria became “obsessed” with finding Paul.

“I tormented the Tusla social worker,” she admits. “She told me there was a letter from Paul’s adoptive family, but would not tell me what was in it.”

Maria and Mark decided to do their own detective work to speed the process along. They went to the General Register Office in Dublin and asked for any records of babies adopted in 1980. They were handed a massive book listing 10 years of babies adopted in Ireland. They sat down with the book and a ruler and moved through the pages looking for their baby’s date of birth, then checking the sex of each adopted baby born on that day. They left with three reference numbers for three adopted baby boys born on that date.

Could they access adoptive certs for those babies to find out where and when they had been adopted? They were told that yes, they could, at the Roscommon-based register of births of adoptive babies.

Maria travelled there next day, not knowing what information she would get, if any.

“I handed in the three references [for the three baby boys born on Paul’s birth date] and she asked would I like originals or copies of the adoptive certs,” Maria says. “That was it. I came away with adoptive certs for three babies in three different counties.”

By matching bits of the identifying and non-identifying information from General Register Office, the Roscommon registry of adoptive babies and the Adoption Authority, Maria and Mark were left with one name - the adoptive name of their baby boy.

The back of his head on facebook

Everybody was in on the search by now, and friends and family took to facebook in the search for clues.

“(My husband) Mark saw the back of Paul’s head on a facebook page and said - that’s him,” remembers Maria. That was August, 2016.

Though they now had a means of contacting Paul over social media, Maria called a halt, and contacted Tusla to see about arranging an official contact process.

The Tusla social workers met Maria on her own, then her and Mark together, then with their kids.

Maria gave them a letter and a photograph of herself to give to Paul. She read the letter to them so they would know the contents, and asked that they post it to him. Tusla decided against doing so. They said that they had already sent him a letter saying his birth mother was looking for him. He had rung them back to say he was delighted, and willing to meet. Tusla said they had then offered to arrange a meeting but Paul, on his girlfriend’s advice, decided to wait.

Maria said she understood why he might want to wait a bit before meeting, but asked again that Tusla send him the letter with her contact details, and her photograph, in the meantime.

“I thought that should be up to me - I wanted him to have that information,” she said. “I could have posted it myself - we knew his address at that point - but I thought it would be better coming from the professionals.

“They said they would not post it. My heart just sank. I didn’t want to jeopardise what I’d waited years for (though) I was happy he was alive and in Ireland.”

Having come so close that August, the end of the year was approaching and the family were no closer to meeting Paul. Mark had had enough.

Unbeknownst to Maria, he used social media to make contact with Paul - and Paul responded. Father and son began messaging each other. When Maria happened across the messages she admits: “I went mad.” She was afraid that after so long, the effort to reconnect would go awry.

Telling their son their story for the first time

In fact, it didn’t work out that way. At the end of January 2017, Maria and Mark finally met their first son at a hotel in the west. He met three of his four siblings about four weeks later, and the final one, who lives abroad, shortly after.

“It was the most wonderful feeling in the world when he walked into that room,” Maria said, with joy in her voice. “It was so easy. I’d thought there would be gaps in the conversation - Mark promised he’d fill them if there were - but there were no gaps.

“I was able to tell (Paul) the full story for the very first time. All he knew was that his mum was young when she had him. He knew through the social media contact with Mark that he had siblings - I was able to tell him about the four of them. It was just - wonderful.”

In the year since, the family have grown very close, and are in frequent contact. “Seeing them walking down Grafton Street side-by-side...I don’t know how it is but he walks just like his dad,” Maria laughed.

“The last year has been absolutely brilliant, like a missing piece of the jigsaw slotting right in.”

Mark is waiting for a time that feels right to tell his adoptive parents that he and his birth family have reunited, which is why all names have been changed in this story.

Maria said she felt frustrated by the state agencies’ response to her efforts, and that she was able to achieve more with her own detective work than the state agencies. That being the case, she said Tusla needs to speed up its processes to facilitate meetings between birth parents and children.

In her case, she feels Tusla never adequately explained its decision not to send that critical letter to Paul in August 2016, in which Maria introduced herself and her family.

“Ours turned out to be a lovely story, but they’re not all lovely stories,” she said. “It’s a very emotional process - a rollercoaster really - and some people can handle that better than others.”

She advises any birth parent seeking their child to do their own detective work in parallel with having queries in with the State agencies.

“The system is so slow, and it shouldn’t be, especially not where all parties are adults,” she said. In particular, she feels strongly that Tusla should have sent her letter to Paul in which she set our all her contact information and the bones of the story of his birth.

[h2]Still waiting[/h2]

At the end of March, 2018, there were 649 people affected by adoption awaiting a Tusla information and tracing service. In a statement, Tusla said: “(We are) very aware that when attempting to source information or trace family members, many people may wish to and everyone is entitled to carry out their own searches. However, Tusla encourages people to consider using the services of accredited agencies to ensure that the information they get is correct. When people search through agencies, they also have access to additional supports at what is a very emotional, sensitive and often stressful time and benefit from staff’s mediation skills.”

Maria acknowledges too the fact she and Mark were Paul’s birth parents, were still together and were both committed to finding him, removed potential complications and provided each with the support of the other.

Of their happy ending, Maria says: “I’m like a new person now. I’m so much lighter”, with a ring of pure joy in her voice.

If you have been affected by the issues in this article, you may find the following links useful:

The Adoption Authority of Ireland

A list of the records held by Tusla and their locations is available on the Tusla website here.