Financial discipline on infrastructure projects must be maintained, writes Kyran Fitzgerald.

A civilised society must cherish its children, but does our Government really have to display its commitment to its sick young by throwing all caution to the wind when it comes to capital expenditure control?

The budgetary overrun on the National Children’s Hospital project can be put down to a number of factors. Pressures on the construction front has led to an upsurge in building inflation.

Endless planning delays have not helped.

The Department of Health and the HSE have never had to cope with a project on this scale before. You really only learn by doing.

But difficult questions must be asked of those involved, starting with the Taoiseach and his Minister for Health, Simon Harris.

Both men have signalled a high degree of emotional commitment to a project which has the backing of the vast majority of the Irish public.

Politicians, these days, are required to display their caring side, but those with experience will know that it is a hard world out there, one where the vulnerable tend to be taken advantage of.

When a minister sets out his or her stall and states that no expense will be spared when it comes to a project, one can sense trouble ahead. Suppliers pick up the scent of vulnerability.

Extra items are added to the invoices which, people sense, will not be questioned too closely.

Over time, cost estimates just balloon.

In the case of the Children’s Hospital project, they have soared from €650m to more than €1.7bn at the latest count. Where is the end point, one wonders. €2bn? Who knows?

You have to wonder, when the project was first being promoted, whether the initial figures being bandied about had much in the way of reality about them. Selection of an expensive location, no doubt, has been a contributory factor.

This comes on top of a highly expensive dry run at the Mater Hospital a decade or more ago.

Endless issues with ongoing planning — a real constant bugbear in Ireland — have added to the accumulation of delay. Residences near the St James’s site have to be appeased.

Employees and families must be properly accommodated. Medics produce plenty of well-meant, cost-augmenting suggestions.

The client keeps coming back with new changes in specifications, the sort of thing that drives builders and engineers insane.

It is always interesting to check out how such matters are sorted overseas.

The US could not be accused of having in place a healthcare system where principles of thrift receive priority. However, providers have succeeded in bringing capital projects in on time and within budget.

One example is the 137-bed Nemours Children’s Hospital in Orlando, Florida, which was completed in 2014 at a cost of just under $400m (€350m).

An advisory council was set up before construction commenced with the aim of involving parents whose children would be using the facility. But through the project, a rigorous distinction was made between ‘nice to have’ and ‘must have’ facilities and services.

Put simply, regulatory compliance and patient safety issues were in the latter category.

‘Nice to have’ ideas had to be rejected. Such a no-frills approach may appear less than humane, but in a project-rich environment, tough choices must be made.

There is now a real danger here that badly-needed projects, ranging from primary care facilities to upgrades to outdated existing facilities, will be long-fingered, if not indefinitely postponed.

Most of our public hospital and care home users are drawn from the ranks of the frail elderly and they, too, are entitled to decent physical surroundings and attentive nursing care.

Broader questions have emerged. Does the public sector have sufficient technical expertise available in-house to enable them it to cope when such projects of unprecedented scale are being pressed ahead?

Amid much fanfare and trumpet a highly ambitious capital programme was unveiled during the year.

If budgetary discipline cannot be maintained across a series of complex infrastructure projects, how many will actually see the light of day?

In an increasingly tight labour market, it is becoming harder to attract top-quality people into the public sector without risk of a breach of public pay guidelines.

Looming industrial unrest in the health service, where serious cost overruns are already a fact of life, serves to remind one that the finance minister has little if any room for manoeuvre.

Creative thinking is required when it comes to the recruitment of experts to the service.

In recent years, figures from the private sector — such as senior lawyer John Moran who later headed up the Department of Finance — have been attracted into the public sector for a while.

Such cross-fertilisation can work to the benefit of all provided proper ethical controls are applied. The net could be cast wider in order to attract expertise from mainland Europe, for example.

Those involved in implementing ongoing financial controls must be accorded much more respect within the political system.

The current system of controls, led by the Office of the Comptroller and Auditor General, may need to be upgraded.

Ministers, too, should be rewarded when they set about implementing reforms, seeking to tighten the nuts and bolts of the system.

Justice Minister Charlie Flanagan took a real risk in appointing the senior PSNI officer, Drew Harris, to the post of Garda commissioner amid protests led by Sinn Féin, in particular. A series of detailed reforms are in the pipeline.

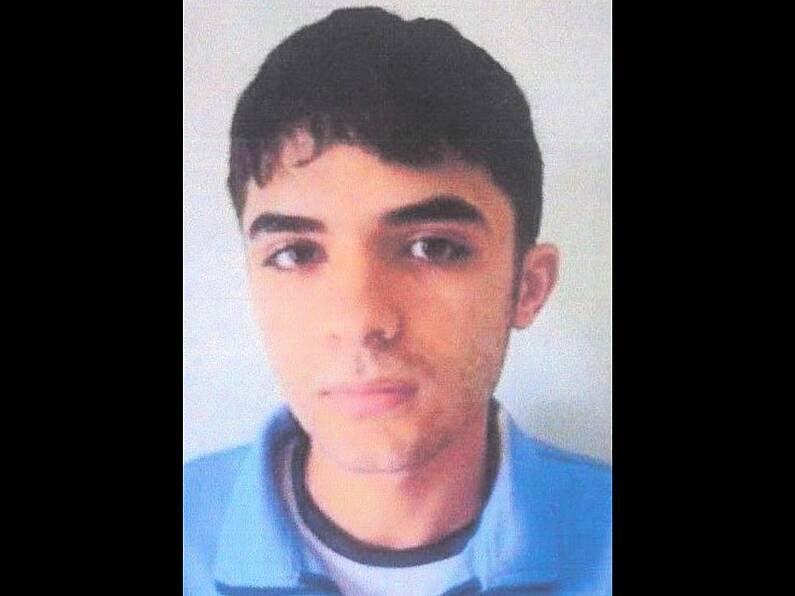

Garda Commissioner Drew Harris

Mr Harris faces a big challenge as he sets out to transform the culture of An Garda Síochána, an organisation traditionally held in high regard by the public, but one that has suffered huge reputational damage in the wake of the Maurice McCabe affair and the findings of the ensuing Charleton Tribunal.

Organisational reform is not sexy, politically. We take for granted the government departments and agencies that perform effectively. Hats off here to bodies such as the IDA, Teagasc, and Bord Bia.

What we are talking about are the nuts and bolts, the underground pipework of government.

Why do some arms of government perform strongly while others fail?

Is it about the prevailing culture, or the personal skills and determination or lack of such of the serving minister?

As we head into very choppy waters, we are likely to discover a lot more about the organisational effectiveness of our various public bodies and it is likely that not all of what emerges will be pleasing to the eye.