Boosting the income-earning capacity of the lower paid through enhancing skills and promoting the creation of enterprises is the way to go, writes Kyran Fitzgerald

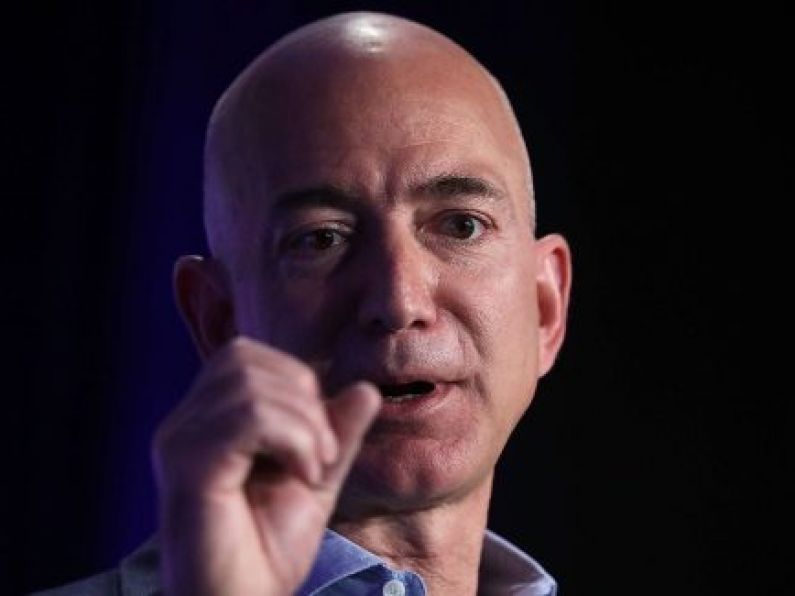

Amazon boss Jeff Bezos has — not for the first time — put the cat among the pigeons, this time with his announcement that the minimum wage for all of his US employees will be raised to $15 (€13) an hour, or around twice the US federal national minimum wage.

Up to 350,000 workers, including around 100,000 seasonal workers, will be affected. The move has caused tremors across the US service sector but is not entirely unexpected.

Retail and distribution rivals will be forced to dig deep to ensure that they can continue to attract and retain employees.

The US economy, boosted by Donald Trump’s tax cuts, is going full steam and the unemployment rate has fallen to its lowest level since 1969.

Demographics in the form of an ageing population and the ongoing crackdown on immigration have played their part in the decision. Economist David Neumark has summed the situation up: ”Low-paid workers, who get kicked the most in a recession, generally benefit later in a boom.”

Their time may have come, but will these same workers find that this new largesse is quickly snatched away in a downturn down the line? Retailers employ a sizeable share of lower-paid US workers and the picture is pretty similar in Ireland.

There are plenty of parallels right now between the Irish and US economies. Ireland is close to full employment and is experiencing all the associated growing pains in the form of high housing, transport, and childcare costs.

Here, much of the recent focus in Government in tackling in-work poverty has been on ensuring that a floor exists when it comes to the payment of wages. In January 2016, the national minimum wage was raised from €8.65 to €9.15 an hour.

Earlier this year, the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI) published a study aimed at addressing the question of whether the increase had resulted in job losses at the bottom end of the labour market. The ESRI concluded that this was not the case. This is an important finding.

Last year, an estimated 7.5% of the workforce earned the minimum wage or less than it. This proportion, however, rises to almost 30% in the case of those working in accommodation and food, and 17% in the case of those employed in wholesale or retail.

Governments enjoy hiking up the minimum wage. It looks good. It boosts employee spending power. It potentially reduces the drain on the State in the form of Family Income Supplement, or, to an even greater extent, rent and mortgage supplement.

However, despite the ESRI findings, the Low Pay Commission is cautious when it comes to sanctioning further increases in the national minimum wage.

It has suggested that such increases be gradual, given that our current national minimum wage is the highest in the EU in absolute terms (though the cost of living, here, is also very high).

The commission has proposed an increase to €9.80 an hour. The most effective way of ensuring that the incomes of the lower paid are raised is to ensure employees get access to training and education, and access to alternative employment. Right now, it is of particular importance that jobs agencies, particularly those run by the State at the local level, function with maximum efficiency and that they target the efforts at those who have come to Ireland from overseas to work here.

Many have skills which can be of benefit to a wide array of employers and many are highly motivated and willing to increase their skills. Finance Minister Paschal Donohoe may likely seek to extend benefits in tomorrow’s budget for the self-employed. Such a move would be more than welcome.

Typically, the discussion on low pay tends to focus on the position of employees, particularly those who are unionised, and those working in the public sector.

However, a considerable proportion of people on modest pay are in self-employment, many of them either young or female with caring responsibilities.

Our media culture is typically fairly neglectful, if not dismissive of the self-employed. The trade unions — understandably perhaps — target their activities at employees, not sole traders.

However, the plight of many self-employed, including owners of firms, came to public attention during the cash when sectors such as construction imploded and multiple firms went to the wall on a daily basis.

The number of people in self-employment fell from 349,000 in 2008 to 285,000 by late 2011, of which just under 200,000 were self-employed people without paid employees. Many struggled. The bald statistics do not capture the individual stories of heartbreak and family struggle, including breakup caused by financial pressures.

Happily, the numbers in self-employment appear to have recovered to pre-recession levels, as construction ramps up and various service activities achieve buoyancy.

However, serious anomalies exist when it comes to State supports for those working for themselves or running small businesses.

But many businesses struggle, particularly during the start-up phase and of course, failure rates for businesses are high.

The Citizens Information Board (CIB) has been to the forefront in highlighting the gaps in provision for entrepreneurs. It noted concerns over difficulties when it comes to securing eligibility for medical cards for the self-employed who are also not eligible for family income supplement, often a lifeline for low-paid earners.

In 2017, almost one-quarter of male earners were self-employed compared to 8% of female workers.

Thirty years ago, PRSI was introduced for sole traders who as a result, became eligible to receive pensions.

This system has proved a boon for many. However, the self-employed in Ireland are not eligible to receive cover in the event of illness or incapacity. This contrasts with the situation in many EU states such as Germany, Italy, France, Denmark, and Poland.

The minister is faced with serious constraints but he must surely begin to move to address such anomalies. Agencies such as Enterprise Ireland do seek to address the needs of entrepreneurs in high-growth industries but a large proportion of the self-employed, particularly outside large cities, tend to operate closer to subsistence levels.

The problem of low pay is a complex one and it cannot be viewed in separation from the broader issue of opportunity. Trade unions exist to ensure that workers enjoy a reasonable set of rights including decent reward starting with a living wage. However, their reach is by its nature confined and as a result of trends over the past few decades, mainly concentrated in the public sector.

Employees in Amazon have benefited from the largesse of Mr Bezos (though the company has withdrawn profit-share arrangements which benefited long-serving productive employees).

We should, however, overly rely on the goodwill of a small number of business barons, however well-intentioned, or strategic. In the hard world of business, what is given is easily taken away.

Far better to act to boost the income earning capacity of the lower paid through enhancing skills and promoting the creation of enterprises.